How big is the Fastest Gun in the West bias?

(Originally published on Meta Stack Exchange.)

One of the earliest phenomena noticed in Stack Overflow’s voting system is the FGITW problem: the first answer is more likely to get upvotes than subsequent answers. Even if later answers are objectively better, the first answer forms a bandwagon that collects more votes than it otherwise would. (One of my earliest and most upvoted answers falls victim to this… sort of.) The bias seems well known, but I haven’t seen anyone actually measure it.

How much does it cost to be the second person to answer a question rather than the first?

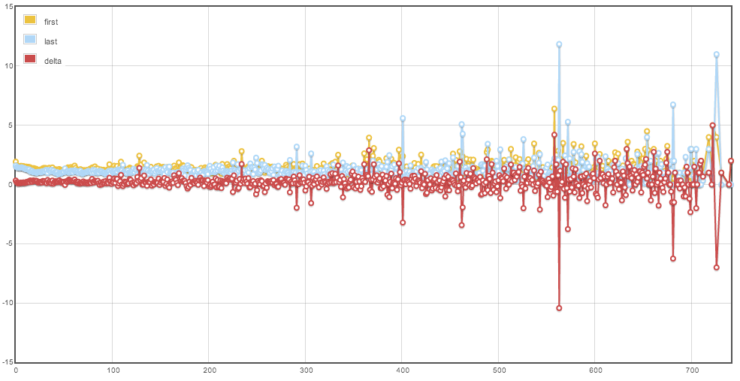

I decided to look at all questions with exactly two non-negatively scored answers. The first answer is declared the fastest gun and the second answer’s score is subtracted from the score of the first. Assuming there’s no other systematic reason the first answer should be qualitatively better1, the difference measures the bias. Obviously, the bias isn’t really a problem when answers are months or years apart; nobody answering this question today can hope to get the top answer in any reasonable timeframe. Indeed, if you look at answers a month apart, noise obscures the bias pretty thoroughly:

The horizontal axis is the hours separating the answers from 0 to one month. Yellow is the average score of the first answer and blue is the score of the answer provided x hours later. Red is the difference between the earlier and later answers. (The image is linked to the query I used to generate the graph.) If you take the average delta over this period, the first answer has about a quarter of a vote advantage. But the data is also very noisy the further apart answers are separated in time. There’s good reason for that: the scale of the FGITW problem is minutes and seconds, not hours and days.

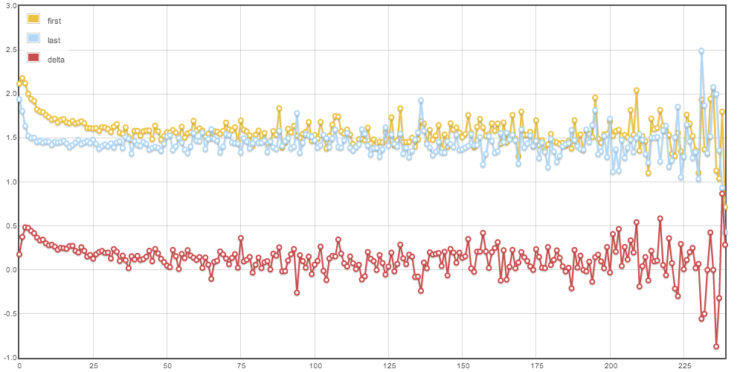

This version shows answers separated by minutes up to 4 hours. Again there is a lot of noise on the right side of the graph2, but the FGITW effect is quite clear on the left side. While the effect is small, it starts at less than a minute difference, reaches maximum effect at about 2 minutes, and more or less disappears by half an hour. The average over 1 to 5 minutes (which is when the bias is most noticeable) turns out to be a 0.43 score delta. Assuming no downvotes, that works out to a little over 4 reputation points per question answered. Over many answers, the bias adds up.

I hope I’ve convinced you that the bias is real and significant. Now I want to argue that we probably don’t need to worry about it nearly as much as we have. As I looked at the data, the sort of remarkable thing I noticed is that the advantage of being first doesn’t really increase the later the second answer gets. Indeed, if you average over all time (by removing the and datediff(minute, f.CreationDate, l.CreationDate) between 1 and 5 clause), the difference between first and second answer is 0.47. Intuitively, we’d expect an answer posted 3 years after a question is asked would never catch up. Answering an old, answered question draws more votes to the existing answers thereby compounding the first-answer advantage.

For popular questions, that’s likely true. But for the vast majority of answers, the half-vote disadvantage ought to be overcomable with a superior answer. For questions with a thousand or fewer views, the bias drops down to 0.353. For long-tail questions, there’s no reason not to write a “second opinion” if you have one.

Meanwhile, there’s real value in providing an answer to a programming question a few minutes earlier. Task switching has a real cost and there’s something to be said for providing an answer to a programmer’s question as quickly as possible. And we’ve completely ignored the risk of answering quickly: misreading the question, getting a few quick downvotes, and having your answer deleted as “not an answer”. The gunslinger lifestyle is hard, fast, and dangerous. Only the best survive long.

This may not be an accurate assumption. There’s good evidence that top programmers are good, nay excellent, at all aspects of the job—including typing. If you add in a few other factors like being able read code more quickly and recall off the top of their heads the quirks of a programming language, the bias I measure may be overstated.↩︎

It would help to use a log time scale. But those are awkward and we really only care about the left side anyway.↩︎

Obviously this isn’t entirely fair. Throwing out the most popular questions also tosses away some heavily voted answers. But my point is that you don’t have to try answering popular questions if you are worried about the FGITW. Answering slightly more obscure questions can be both valuable to human knowledge and rewarding in terms of reputation.↩︎