Ask not what a community is worth . . .

CMX recently released “The 2021 Community Industry Report” and I have thoughts. I’m gonna focus on this one chart that summarizes Community Management in 2021:

I was one of the 503 people who answered “What are your top frustrations about managing your community and its activities?” The top 5 answers were:

- It’s hard to quantify the value of the community (45%)

- It’s difficulty to consistently engage members (43%)

- Our efforts are largely manual and not automated (37%)

- We don’t have enough staff (28%)

- We don’t have enough budget (20%)

There are other answers, but these are the frustrations I’ve had as a Community Manager too and they intertwine. So let’s start with the problem of engaging members of the community.

One of the great things about Stack Exchange is that it’s not one community, but multitudes. Communities for high-level mathematicians, people people, literature enthusiasts, anime & manga fans and do-it-yourselfers might share a platform, but not cultures. Some community initiatives work better with some groups than others. So part of the job is just figuring out what might excite a specific group of people with a common interest. And that means spending time getting to know those selfsame people.

Even when we had a good understanding of the communities, it’s not easy to predict how people will respond. Community management is, in fact, a Dunning-Kruger trap.1 Until you’ve done it, you can’t know how much skill it requires. How hard can it be? You sit around on social media, forums and chat making jokes, right?

Unfortunately, it’s not always possible to cause communities to form how or where we might want them. For instance, there were two topics that seemed a natural fit for Stack Exchange that we just couldn’t make work: Artificial Intelligence and Startups. Both had the novice/expert disparity problem.2 There were plenty of excited amateurs and sufficient enthusiastic professionals. But the questions tended to be the same sort of questions people ask when they first get interested in the topic so the experts were bored giving the same answers they gave at cocktail parties or whatnot.

After several attempts, there now is an active AI site. Robert Cartaino, who ran the Area 51 process for forming new Stack Exchange sites, gave that proposal a chance because AI has matured beyond its theoretical beginnings. Questions are now firmly rooted in techniques that emerged from AI ivory towers. Now that anyone can start working with neural networks, machine learning and standardized AI libraries, there are on-ramps for the new user to ask questions the experts want to answer.

That didn’t happen with startups. Even if it had, there’s no reason to think the audience would have stuck around. My guess is people who want to start new companies tend to move to the latest thing. I wouldn’t be surprised if questions about startups recently moved to Clubhouse. Most likely they will soon move somewhere you and I haven’t even heard of yet. Cultivating a sustainable community often depends on factors outside of our control.

That brings me to the top concern: how can we put a value on community management? To answer that question, consider a hydroelectric dam.3 This is perfect because I don’t know how to operate a hydroelectric dam and, unless I’m very unlucky, neither do you. I imagine when a dam manager gets evaluated, the primary metric is how much electricity did the plant generate and how much did it cost. The equivalent for communities is, according to the survey, new customers and customer retention.

My family visited the Bonneville Dam4 a couple of summers ago. Wandering about the visitor center, it was pretty clear the facility produces much more than electricity. I mean, it’s impressive to see a long row of generators capable of providing enough electricity for the city of Portland,5 but to quote their website:

Today, the project is a critical part of the water resource management system that provides flood risk management, power generation, water quality improvement, irrigation, fish and wildlife habitat and recreation along the Columbia River.

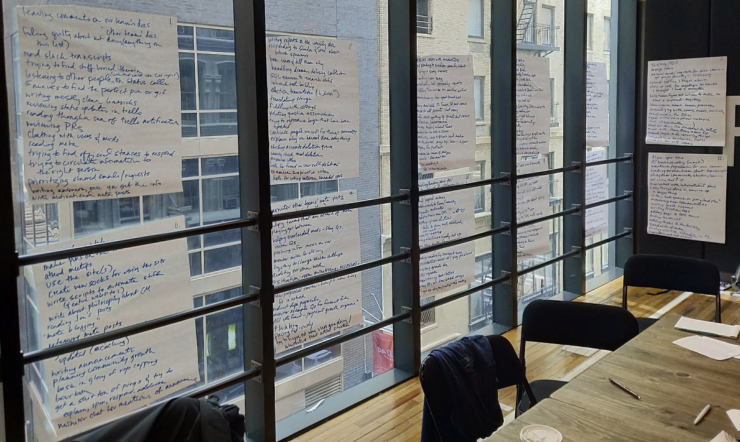

That’s a lot of responsibilities and it doesn’t even mention the visitor center and gift shop! At one Stack Exchange meetup the community team tried to list all the things we do and after filling many of those sticky poster things, we still missed a few tasks. Having a long and diverse set of responsibilities is one way community managers are exactly like dam managers. (I doubt that title even exists,6 so hopefully nobody will disprove my assertion.)

Now suppose the executives in charge of Bonneville Dam looked a the budget and wondered if they could save some money. “What if,” these hypothetical execs said, “we just didn’t do some of the things on this list? For instance, what if we stopped maintaining the fish ladder? Not forever, mind you. Let’s try it and see if anything breaks.”

Seems to me that this policy would work pretty well for quite a while. The fish ladder mechanisms seem sturdy enough. Maybe volunteers from the community would come out to take care of it? However, that’s not something I as a person who knows full well I know nothing about fish ladder maintenance would ever suggest. The cost of being wrong could be catastrophic for the fish species that depend on it.

So much of community management involves doing things that don’t have an immediate benefit, but not doing them could be disastrous. Or maybe it’ll be fine. Critically, nobody can truly know since communities aren’t made up of physical parts, but of human agents. People, whatever their faults, rally around communities they love and take care of each other. Companies can benefit from this fact for a long time without putting much effort at all to sustain them. Until, seemingly for no reason, the community is gone.

This gets us to the budget and staffing concerns. When companies spend less on community, there’s rarely immediate feedback other than cost savings. This leads to a false sense that a community team reduction leads a more efficient team. But “efficient” often means eliminating tasks that don’t have a clear or immediate purpose. At Stack Exchange, after a round of layoffs that cut the community team by ~20%, we decided to reduce the time we spent in chat with moderators. We were worried that moderators would complain, but they generally seemed accepting of our change of process.

But that change came at a cost. It just took several years for the damage to be revealed. The community team didn’t know that this would happen. But we suspected it wasn’t going to be without consequences. When there are concrete cost-saving benefits and uncertain future costs, CMs become like the prophets confronting the kings of ancient Israel:

And He said, “Go, say to that people:

‘Hear, indeed, but do not understand;

See, indeed, but do not grasp.’”—Isaiah 6:9

Fortunately this is a problem many people are working on. We’re starting to see some clever ways to measure the value of community. For instance, Richard Millington showed the community around a large tech company was saving nearly $3 million a year in support costs. Stack Exchange can put a value on CMs spending time chatting with moderators by adding up the cost of initiatives intended to restore community trust.7

Building a community is like building a hydroelectric dam: the enormous upfront cost produces sustainable value for generations if well maintained. Community professionals are being asked the wrong question. Putting a value on a community is exactly the same as valuing a city! The naive answer is to look at how much the city government raises in taxes. And yet companies routinely reduce the value of a community to the revenue they can extract from it. That represents a fraction of the true potential value to the company to say nothing of the value to humanity.

A better question to ask is what do we need to invest in order to maintain the community? That’s a question community managers are equipped to answer. If and only if you’ve committed to maintain the community can you begin to explore how you can profit from the community. It’s the simple test of whether a company really puts community first.

Important note: I wrote almost all of the above a few weeks back when I was working for College Confidential. Now that I’ve left I should clarify a few things that might be misunderstood:

Valuing community often means investing more in community management. But some communities, especially established communities, can function independently. In addition, companies can invest in community by doing things like improving the community software, encouraging employees who aren’t community managers to get involved or changing their business model to be less intrusive.

The College Confidential community is in pretty good shape for the moment. I admire and respect the current owners. I believe they will not only sustain the community, but grow it over the next few years.

My experience at CC gave me insight into what really helps online community health. It’s early yet, but one of the ideas I’m considering is starting a consulting business that replicates the success I had with CC to other communities.

One could argue that all types of management trap people in similar ways.↩︎

Arguably Community Building has the same problem. In fact, the bottom of this list seems filled with this problem.↩︎

As I was writing this, I noticed Richard Millington compared communities to nuclear power plants.↩︎

The Bonneville Salt Flats and the dam were both named after Benjamin Bonneville in case you were wondering.↩︎

Which, coincidently, it does.↩︎

I was wrong. In fairness to myself, that’s not what I meant, Google.↩︎

Plus a bunch of other “cost-saving” measures that left Stack Overflow and Stack Exchange members feeling abandoned by the company. None of this counts the unknowable opportunity costs.↩︎