If more users could vote, would they engage more?

(Originally published on meta Stack Exchange by Jon 'links in bio' Ericson.)

Stack Exchange is facing an existential crisis . . .

and it has been for some time.1 Back in 2014, I proposed 4 attributes of a healthy Q&A site based on a 2011 ACM paper:

- Number of active users,

- Percent of questions answered,

- Speed of answers, and

- Question views.

The first and the last directly impact the company’s bottom line and the middle two matter to users. In 2016 gerrit noticed answer rates falling on Stack Overflow. Median time to first answer was also rising, but that’s a lot harder to suss out from just using the site.

And then it became quite obvious that you can get faster answers from ChatGPT than from asking on the internet. LLMs always answer your question and it can be argued that since they use a massive corpus, the number of people contributing to each answer dwarfs the competition. Shame that the answers are simplistic and buggy, of course. Still, you can always ask again and maybe you’ll get lucky.

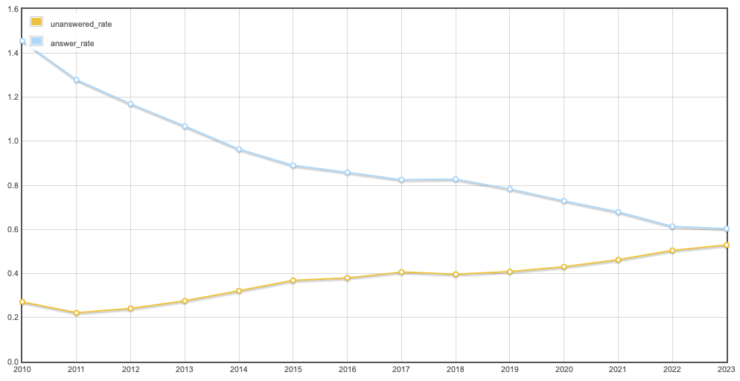

It’s important to see that ChatGPT was the catalyst and not the cause. Q&A sites can thrive if there’s a reasonable chance the asker will get an answer before the problem is overtaken by events. Stack Overflow sucks up a lot of the attention, so let’s look at Mathematics instead. Here’s a graph of the average number of answers per question and the rate of questions that go unanswered after 30 days on that site:

This is not as scary as Stack Overflow, but it’s nearing the point where getting an upvoted answer to a good question2 on Math is about the same as flipping a coin. Since getting answers is the best encouragement for asking another question, this is a particularly detrimental to a Q&A site.3

There’s nothing sacred about the voting model

I was a beta user on Stack Overflow. As such, I was invested in the project of creating a community for programmers. Thankfully my argument for not having closed questions did not win the day. But Joel and Jeff did take suggestions from the community. In order to get the site up and running, they also made decisions based on educated guesses of what would work rather than any sort of scientific experimentation or data analysis. Given the tremendous success of Stack Overflow it’s easy to assume those choices were correct.

Still, even if those decisions were perfectly tuned (they weren’t) a lot has happened in the past 15 years. It’s important to verify that assumptions made in the past still hold. For instance, did you know there was a time when people worried that Stack Overflow might become “brainless LOL-fest like Reddit or Digg”? Five years later someone commented (incorrectly) that people without reputation weren’t able to ask questions at all. Pretty sure the network dodged the mindless fun bullet.4

My point is that it would be foolish to not question or test the assumptions made early on.

Letting new users vote probably won’t make much difference

When the feedback mechanism was introduced, it was a separate UI from the voting mechanism. At some point, the voting interface was repurposed for anonymous and low-reputation users to count as feedback. (Certainly by May, 2013. Probably late February of that year.) But it’s never counted as an actual vote. Indeed, the action is recorded in an entirely separate table (PostFeedback) than regular votes (Votes on SEDE and Post2Votes, if I recall correctly, internally).

The proposed change moves the votes from registered users who can’t vote because of reputation limits from the feedback table to the proper votes table. It also subjects these votes to all the restrictions of a real vote that (as far as I know) feedback is not subject to. For instance, votes will be rate limited and trigger voting fraud checks. So at least initially, there will be fewer votes than feedback events recorded. Over time the number might increase as users discover their votes now count.

So how many votes are we talking? For the week of 2023-07-04 on Mathematics, there were:

| Week of | Vote Type | Daily Average |

|---|---|---|

| 2023-07-04 | UpMod | 1350.857142 |

| 2023-07-04 | DownMod | 267.571428 |

| 2023-07-04 | AcceptedByOriginator | 93.142857 |

| 2023-07-04 | ApproveEditSuggestion | 51.714285 |

So ~1,300 upvotes and ~270 downvotes a day. Here’s the post feedback for the same week:

| Week of | Vote Type | Daily Average |

|---|---|---|

| 2023-07-04 | Anonymous DownMod | 1278.428571 |

| 2023-07-04 | Anonymous UpMod | 795.571428 |

| 2023-07-04 | Registered DownMod | 1.285714 |

| 2023-07-04 | Registered UpMod | 1.142857 |

Since we can differentiate between anonymous feedback (I believe tracked by IP internally) and low-reputation user feedback (tracked by user ID), we can see that visitors click the downvote arrow almost as many times in a day as voters upvote. People who find posts via Google, are much less inclined to select the up arrow in this sample. But the number of registered users who have attempted to vote before they have enough reputation is a tiny fraction of feedback. As in, I rounded off more when I summarized the vote averages just now. So if Mathematics volunteered for this experiment, most people wouldn’t likely notice any difference. I haven’t found any sites that show different results when I use this query.

No silver bullets and no poison pills

So why bother? I suspect the people who make strategic decisions at Stack Exchange Inc. view this as low-hanging fruit that will make a small difference with minimal work. But there’s also a chance that this experiment will suggest other solutions to the problem. We’ve learned a lot more about how online communities operate since the privilege system was invented. Indeed, other community platforms learned from the Stack Exchange model to refine the concepts:

- Codidact grants voting based on a quality threshold rather than a generalized reputation score.

- Discourse begins trusting users after they’ve done a bit of reading.

- TopAnswers allows members of the community to vote (or “star”) more posts based on the number of stars received.

These are very different ways of determining when a new user can be trusted. I have significant experience with Discourse’s Trust Level system and it works incredibly well for our community. While forums aren’t the same as Q&A, requiring reading rather than posting seems a better way to bring people into a community. Removing the reputation gate to voting could allow better (or at least different) gates to be considered.

It’s extremely unlikely this change will solve Stack Exchange problems. It’s also unlikely the change will destroy Stack Exchange communities. As important as the privilege/reputation system is for those of us who deeply interested in online community platforms, the details don’t really register for most new users. It’s the accumulation of good incentives that create good communities.

Please direct comments to the original post.

We tend to think of crises as fast moving: tsunami, stock market crash, terrorist attack, etc. If you are facing a slow-moving crisis, you will find it much harder to raise the red flag since people don’t usually feel the pain until it’s too late to do anything about it. I’m obviously writing now because I believe there is still time to make changes that will keep Stack Exchange afloat.↩︎

Note that the questions in the sample had a positive score and weren’t closed or deleted in the 30 days after asking.↩︎

Some might ask why encouraging a second question is valuable if we already have too many questions on the sites. I’d suggest that asking questions is a skill. I don’t have proof, but I suspect the second question is almost always better than the first. I expect asking is also a path toward answering in the future.↩︎

From experience I know someone reading this is thinking of a recent question that strayed into the mindless fun zone and would love to tell me about it. Don’t bother. If you ask 100 people who have heard of Stack Exchange but haven’t contributed whether fun questions are allowed, I’d be shocked if fewer then 99 said anything less than “hell no!”↩︎