Bias

Conscious and unconscious

I’ve been playing around with the Community Notes feature on Twitter. It’s an interesting solution to moderation at scale that relies on humans. For my money (and, I guess, time) it’s the most interesting thing going on the platform right now.

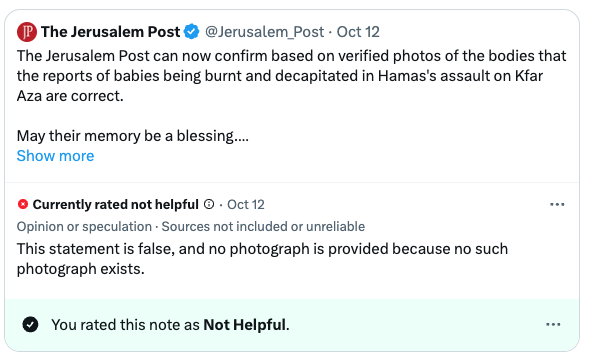

As you might imagine, the Community Notes I’ve been asked to rate lately have tended to involve Hamas’ terror attack. They are, frankly, discouraging. Here’s an example that’s on the mild side:

Unfortunately such photos do exist1 and they are horrifying. But the odd thing is that people seem to have moved the standard. Killing innocents doesn’t cease to be evil when done in a more clinical manner. Systems of morality that encourage the killing the offspring of the enemy exist,2 but modern people universally condemn these beliefs as tribal and racist. So it’s weird that otherwise civilized people would try to justify this particular murder of babies.

Only it’s not at all weird. When we visited the National Museum of African American History and Culture or Manzanar, I noticed I was quietly desperate to provide context. Even this summer, when I was confronted with the injustice my country did against native Americans, I wanted to find any way of reducing my horror of our history. It’s not a conscious choice, but an instinctual rebellion against dealing with feelings of guilt.

Bayesian statistics offers one way to think about the phenomenon via prior probability. Let’s take a (hopefully) uncontroversial example:

- A few days ago my wife and I started shopping for tickets on the Alaska Airlines website.

- The next day I got an email from Alaska Airlines offering me miles if I applied for a credit card and used it to buy tickets.

- What are the odds I got the email because Alaska noted we were looking for tickets a few days ago?

Well, it depends a lot on what I think the odds are that I’d have received the email offer if we hadn’t started pricing tickets. Since I don’t remember seeing an email like this in the past, I assume the odds are quite low. If I only get a few emails, say, once a quarter, then it’s a lot more suspicious than if I get them every day. And everyone knows Google/Amazon/Apple has their digital spies everywhere so that they can sell your data to companies like Alaska Airlines.

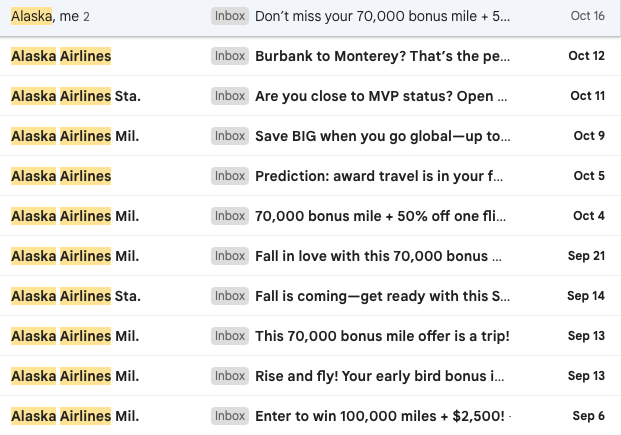

Let’s do a quick search of my email:

Well. Not only do I get many emails from Alaska Airlines, I got nearly identical offers on October 4 and September 13. So much for my hypothesis that searching for tickets caused Alaska to send me that email. I also unsubscribed from the Alaska Airlines mailing list.

If you identify with a group in some way or another, you’re likely to think people in that group are generally good and reasonable people. One bit of evidence will have a really hard time changing that belief. Indeed, it might paradoxically increase your positive feelings about that group. So new evidence rarely changes the way people think about prior beliefs.

When I worked at Stack Exchange, I took an implicit bias test that my boss recommended.3 Like many people I learned I’m unconsciously biased against women and people with dark skin. Then I tried to use that knowledge to change my behavior. What I found is that I might have a bias for a fraction of a second when I meet someone for the first time based on skin color and gender, which is what the test measures, but I very quickly overcome that bias in the following minutes when I get to know someone. Implicit bias for most people is a very weakly held prior that quickly becomes overcome by evidence.

The LA Times published a story titled, “Stanford scientist, after decades of study, concludes: We don’t have free will”. My immediate thought was “No he didn’t!” It’s a logical impossibility because if his conclusion is true he can’t conclude anything at all. It’s just the result of random firings of neurons in his brain. If so, why should we trust his conclusion over anyone else’s? Surely he must carve out a tiny island of free will for his book to stand on. Of course, “We don’t have as much free will as we think we do” doesn’t grab the reader in quite the same way.

So I’m not sure our subtle implicit biases matter much. Because of my upbringing I might instinctively favor some people over others based on superficial qualities. I can’t argue that I should avoid acting on those instincts. However any change I make in that respect will be marginal at best. No, I’m much more worried about my biases that everyone except me is aware of. Those are the patterns of thinking that will lead me down the wrong path even when I’m faced with overwhelming evidence that I’m wrong.

Of course there are Community Notes arguing over whether those images were computer-generated or altered. It strikes me as plausible that someone would do this. I’ve also seen horrific images of children being rescued from bombed out buildings that turned out to be from a 2016 Syrian attack near Aleppo. Kinda illustrates the doctrine of Total Depravity if you ask me.↩︎

For instance Psalm 137:9 advocates the murder of the children of Babylonian occupiers of Israel:

Blessed shall he be who takes your little ones and dashes them against the rock!My Psalm a Day podcast ended before I rached 137 (I do hope to start it up again soon!) so I don’t have complete thoughts on this conclusion. I will say that the entire book of Psalms lives in the complicated world of emotion. It’s not the sort of thing you can apply to your life without introspection.↩︎

Read down to footnote #2 for the link.↩︎