Codenames

No secret to this success

With such a simple concept, it’s hard to believe Codenames isn’t a refined version of an older parlor game.1 Each team selects a spymaster who knows the codename of each team’s agents as they are laid out in a grid on the table. Then the spymasters take turns sending a single word clue and how many cards their team should guess. The first team to have all of their target agents revealed (without guessing the assassin) wins the round. Frequently teams select another spymaster and play again.

Great party games don’t need the safety net of scoring. I vaguely remember Codenames having a score system. When I checked the rules I discovered there is—for the two-player variant. I suppose competitive people would just keep track of how many times their team won. Keeping track of winners and losers just doesn’t add a whole lot.

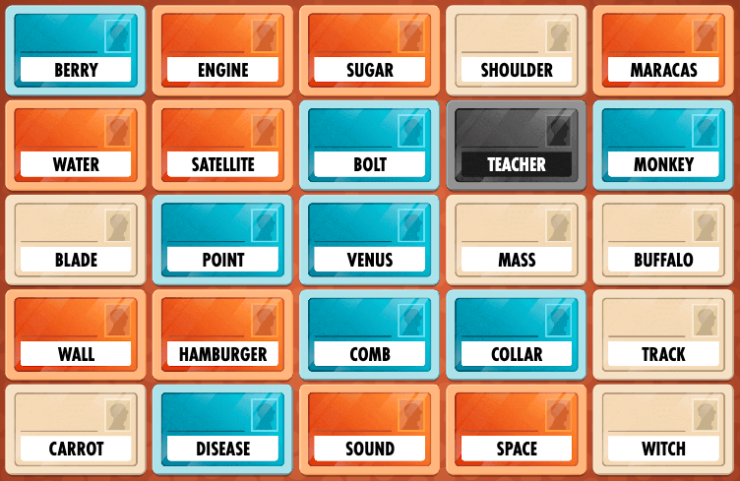

Not that Codenames isn’t challenging. It’s more that the challenge comes from mastering the puzzle each array of words presents. Here’s an example lineup from the Codenames online implementation:

This is what the spymasters of each team will see:

- Red and blue cards are the red and blue agents respectively. Spymasters only want their team to guess their own color and avoid signaling the opposite color, which helps the other team and ends the turn.

- Tan cards are civilians. If they are selected, they end the current team’s turn. That’s annoying, but recoverable. Teams can always make an extra guess and pick up an agent they hadn’t taken in a previous turn.

- The black card is an assassin. Any team that picks that card immediately loses the game.

Their teammates only see the array of cards and not the key that identifies them.

In this example, the red spymaster might notice “space” and “satellite” as easily signaled words. “Rocket” could work as the clue and might even pull in “engine” if you push your luck a bit and say it applies to 3 instead of 2. But then there’s “Venus” in blue, which must be avoided. Or maybe your team will guess “mass” based on a long-forgotten physics class. And there’s always a chance someone will try rope “carrot” in since it has a vaguely rocket shape and partially rhymes.

Or maybe link “maracas” and “sound”? “Music” maybe? Only be careful not to lead your team to try out “teacher” based on music being a subject they might teach since that card is the assassin. Knowing your team helps as a Mozart enthusiast might select “mass” as a musical composition. On second thought, it’s all too easy for someone to pick “track”, which wouldn’t be terrible (just a civilian) but would both end the turn and give the other team one fewer word to think about.

The card layout gives spymasters a puzzle and the spymasters pass a new puzzle to their teams. But not just to their own team. If you see “pox 2” and the opposing team guesses “disease” (correct) and “witch” (a miss), you have a bit of useful information if you remember the brief “monkey pox” scare. Again, it can help to know your audience.

Generally party games become unbalanced with couples or close friends are on the same team. Codenames isn’t an exception, though it does lead to second guessing that can result in disaster. Recently I played with my wife and gave the clue “Salt 3”. My team narrowed it down to these words:

- Himalayas

- Water

- Beach

- Compound

I hadn’t connected “salt” to “compound”, but my wife was right when she said that’s something I was prone to doing. So instead of “beach”, which was a reach, they picked “compound”. It was the assassin. For whatever reason my brain didn’t make a connection it normally would, so we lost. Codenames rewards cleverness and anticipating the thinking of other people. But there’s always a risk of over-thinking things both as a spymaster and as a team member.

When each round starts, it can take a bit of time for the first spymaster to pick their first clue. But after the clues start coming, the game usually moves at a pleasing pace. Everyone is playing on the same tableau of cards, so every move impacts everyone at the table. Each card that gets revealed changes the landscape so that new clues are opened up. While you can get a snack when it’s not your turn, you risk missing an important clue as the other team discuss their options.

Now sometimes a spymaster takes too long coming up with a clue.2 This is sometimes called Analysis Paralysis (AP) and can kill the momentum of a game. Codenames includes a sand timer and very unusual rule for deploying it. Most of the time it stays in the box, but anyone can start the timer if they feel it’s needed. The rules even suggest a spymaster set the timer for themselves so that they have a self-imposed deadline. I love this mechanism because:

- It could easily be added to any game at all and

- It paradoxically gives some players more time to think.

When the pressure is on and you have to make a decision, it can feel like every second is an eternity. Setting a timer does limit your time, but you don’t have to worry you are taking too long. As long as you beat the timer, you’ve kept to a socially-acceptable pace.

At it’s heart, Codenames is a word-association game that’s probably a lot closer to Apples to Apples than I’d like to imagine. The spy novel theme lifts it out of that comparison for me. Card art provides an assist with suave red and blue agents, and confused neutrals. (As an extra touch of class these cards have a male and a female side that have no gameplay significance.) A mysterious assassin card even though it’s not needed: once the assassin is picked, the game is over. It’s always sitting on the table waiting for someone to make a fatal miscalculation.

I’m specifically thinking of Balderdash, which closely resembles Dictionary. It’s an excellent re-implementation.↩︎

Or occationally a team takes too long finalizing their guesses, but this is less common.↩︎