Battle Card: Market Garden

A beautifully simple model of a SNAFU

There is no shortage of games about Operation Market Garden. If you have read or seen A Bridge Too Far, you have a good idea why. It was an audacious and dramatic attempt to shorten WWII by a year.

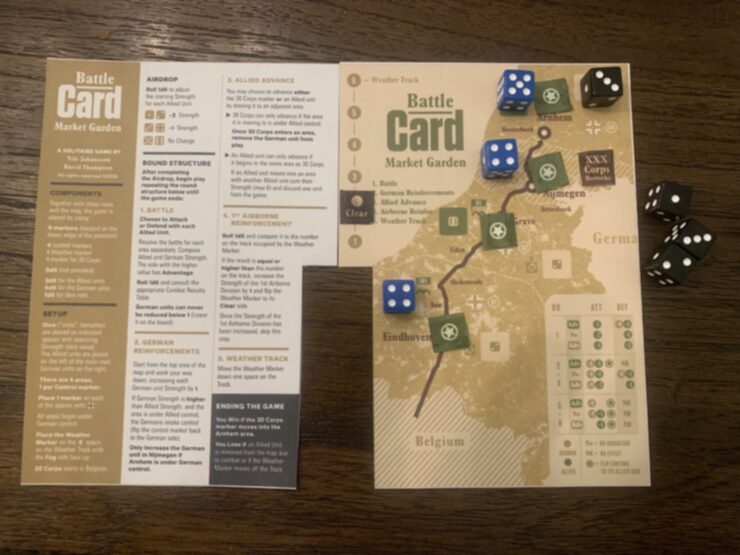

Battle Card: Market Garden takes that complex military operation and abstracts it down to the key turning points. The German defenders occupy each of the 4 control areas. Allied paratroopers drop into the Netherlands and 30 Corps gears up in Belgium. Combat is resolved using a simple Combat Results Table (CRT) which inflicts causalities and flips control markers based on the size of each force, who is attacking and a die roll. German reinforcements arrive on regular schedule and Polish paratroopers wait for the fog to clear so they can join the battle. It looks a lot like a traditional, if small, war game. Perhaps something in the way of The Drive on Metz.

As you look more closely, however, the abstractions feel a lot closer to a euro game. The units are dice, not chits. Instead of hexes, there’s a single path through the four regions. Combat happens in every area with both Allied and German units whether you like it or not. The only decision is attack or defend. The CRT requires only comparing force sizes—there aren’t any modifiers to apply. And, of course, this is strictly a solo game.

The rules consume half a sheet of paper and the map takes the other half. (This is a free print-and-play game.) It really takes 5 minutes or so to complete and can be won with as few as 12 die rolls. After the first game or two, you won’t even need to reference the rules other than the CRT.

I regret to inform you, however, that Battle Card: Market Garden isn’t much of a game. There are plenty of decisions, but almost all of them are forced. While it’s certainly possible to play poorly, the difference between winning and losing comes down to luck more than anything else.

Historical war games frequently exhibit a tension between accurately modeling their subject and providing a balanced competition. Usually designers solve this by giving players freedom to make different decisions than their historical counterparts. For instance, if the 82nd Airborne secured the Nijmegen bridge immediately rather than capturing the Groesbeek Heights, that might have shifted the battle toward the Allied side. In this way war games return to their roots as tools for planning.

The Battle Card system (assuming there will be more entries in the series) abstracts most of those decisions away. Landing is risky and mostly out of the control of the commander. So it’s simulated by a roll of a die for each unit. Fog lifting to allow Polish reinforcements is another random die roll. German forces reinforce on a strict schedule.

The only decisions remaining are:

- Attack or defend with each airborne unit and

- Whether to advance an airborne unit or 30 Corps.

Those decisions are further restricted by the mission goals. The 101st Airborne must attack on day 1 so that 30 Corps can advance into Eindhoven. 1st Airborne should attack in order to control Arnhem and prevent the German forces in the Nijmegen region from getting reinforcements. The only question on the first day is whether the 82nd should defend or attack to gain control of Grave early.

As the situation develops, the decision of which unit to advance down Hell’s Highway tends to be obvious as well. Almost always it should be 30 Corps that advances if it can. Only if you think the 82nd needs to be brought to full strength by the 101st would it make sense to hold back the armor. There’s literally no room to maneuver, which is usually the best part of a war game.

And yet . . . I really enjoy Battle Card: Market Garden. I won’t deny that my interest in the history of this particular battle plays a large part in my fascination with the game. Incredibly this one small package unfurls the drama of Market Garden as you play it again and again. Maybe everything will go right and 30 Corps will be across the Rhine before time runs out.

More commonly, you’ll hit a SNAFU (Situation Normal—All F’ed Up). One time, I had almost perfect landings, the 1st captured Arnhem and all seemed to be set up for victory. And then the 101st failed to secure the Eindhoven area for two consecutive days. Between German reinforcements and combat loses, the Allied airborne divisions lost their numerical advantage and the battle quickly ended.

Frequently 1st Airborne Division bravely fights to hold Arnhem. Usually the Polish 1st Parachute Brigade provides reinforcement in a dramatic fashion. But the armor just can’t make it past Nijmegen in time to save the day. The game is too high-level to simulate details such as botched resupply, broken communications or the Germans detonating bridges. Instead you read between the dice.

As I play one game after another, I wonder how Monty and Ike gamed out the operation during planning. Taken as an abstract model, Battle Card: Market Garden accurately demonstrates the peril of chaining events that must go off as expected to achieve victory. Unless the Allies can hold the bridge at Arnhem before the Germans can respond, the whole endeavor fails.

We tend to assume complicated simulations get better as more details are added. That can be true when the details can be modeled with certainty. Weather models, for instance, get better with tighter grids. But battles swing on details that can’t be anticipated: boats that arrive too late for a planned river crossing or radios that don’t work because of sunspots. Modeling that sort of event creates false precision.

Better to build a simple model that’s broadly correct and can be run many times. Battle Card: Market Garden is just that sort of model and it makes a marvelous tool for learning.

Also posted on Board Game Geek.